It is time to bring back the wax seal

Despite being surrounded by modern communication, the slow, arguably impractical, process of writing a letter is a great draw for me

Snail mail for personal communication is more of a niche interest today than a necessity. It is certainly not as practical as modern-day alternatives and cannot hold a candle to email or internet- and carrier-based messaging services. And this has forced it to become a sort of luxury—of time and money both. Still, the ritualistic practice of writing a letter, sealing it in an envelope, pasting stamps, and dropping it off at a red postbox is a calming, almost theraputic process that I find hard to let go of when I have the opportunity to send someone letters.

Before the ubiquitous gummed envelopes, though, there was the sealing wax. Here is an interesting extract from a December 1893 issue of The New York Times which the paper borrowed from The London Daily News—

In France sealing wax has by no means gone out as a consequence of the introduction of gummed envelopes. According to The Bulletin de la Papeterie, there is even a sort of code or language of sealing wax among fashionable people. White sealing wax is chosen for communications relating to weddings, black for obituaries, violet for expressions of sympathy, chocolate for invitations to dinner, red for business, ruby for engaged lovers’ letters, green for letters from lovers who live in hopes, and brown for refusals of offers of marriage; while blue denotes constance, yellow jealousy, pale green reproaches, and pink is used by young girls and gray between friends.

Leave it to the French to stick to a fashionable old habit after the world has moved on, and to take it to a whole new level with colour codes. The first thing that struck me were the colour codes; having never read about French practices with sealing wax before I was under the assumption that the rules were much simpler: red is the default colour and is also preferred for formal correspondence; black was for mourning; white was for weddings and dinner invitations.

Further, there are seal rules that the Times/LDN article fails to address: the family sigil was used for familial business and personal correspondences; a monogram seal was used for personal or business letters; and mottos and generic decorations (fleurs-de-lis and such) were used for informal, mostly private, correspondences.

All this points to a deep sense of calm in the process of communication. Today most communication takes place faster than it should. Even in case of urgency, the simple act of melting wax and impressing the seal, even if it only took a minute to accomplish, gave a much-needed breather that clicking the ‘Send’ button does not afford.

However, there has rarely been a time when mindless hustling was not central to society: people welcomed the gummed envelope as a replacement to the sealing wax because back then people saw the sealing wax only as a means of sealing an envelope (and quickly identifying types of letters by colour). The gummed envelope solved the sealing issue and did so more efficiently, and the wax was on its way out.

Today we look back at the vintage for reasons people in those times would perhaps never have expected. It shows care and concern and value; it shows a person took time to do this for whomever the letter was addressed. What once was a time consuming chore is now used a symbol of the time and care it demands.

Equally, the sealing wax was once ubiquitous and held no special value. It was routine. In its resurgence in the 21st century, following its demise in the 1800s, the rarity of something that was once as common as a smartphone is today, has made the sealing wax a symbol of elegance, class and care.

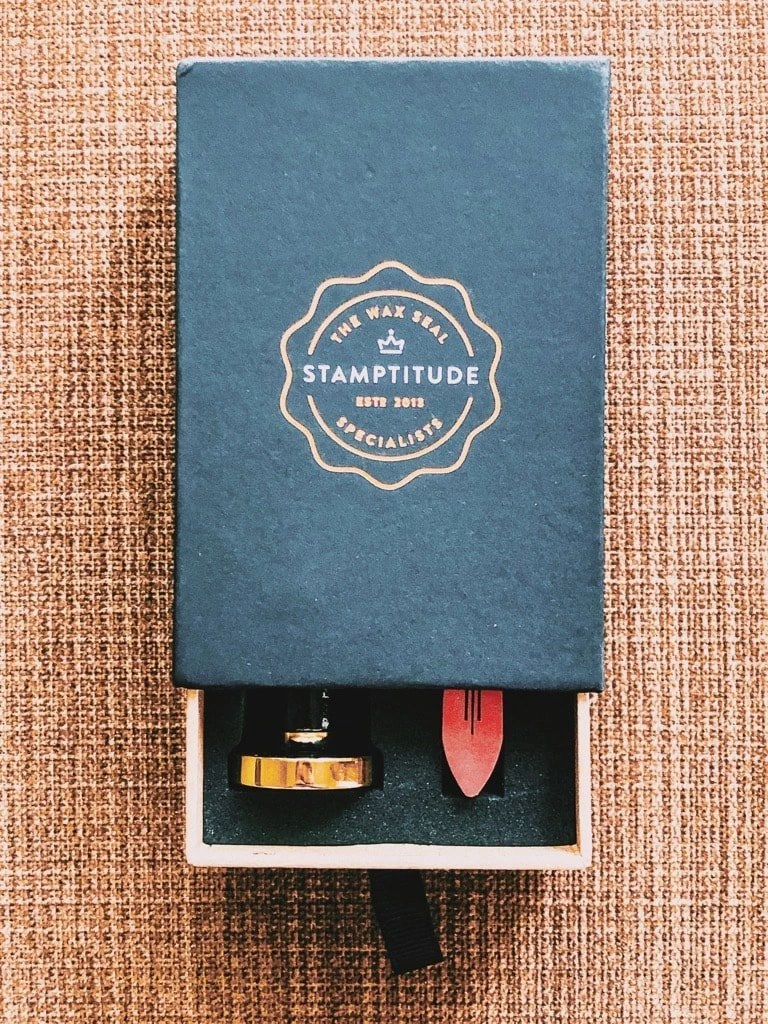

Stamptitude was the first name I came across while looking for custom-made stamps. Their dedication, work and pricing made sure I never sought an alternative manufacturer. They worked with me closely to finalise the stamp design and when it was delivered I was impressed with the accuracy of the etching (no doubt a combination of lasers and computers). I soon realised I probably should also have placed an order for their melting spoon.

Almost as soon as the seal arrived I wrote my wife a letter which I then proceeded to seal with my new … well, seal. I quickly realised that not having a proper melting spoon would cause some problems: there was no way to use a candle and get the wax onto the envelope without a mess, and using matches burnt the wax and paper a bit (see picture at the head of this essay) but on second try, having learnt some lessons earlier, I managed to get a fairly good seal (see picture above).

As I write this essay my wife is likely a day or two away from receiving my letter and does not know about the new wax seal headed her way. But she does not read this website, so it should not be a problem: as someone who loves vintage items like I do, she will still be pleasantly surprised.

The stamp and wax are now tucked away in my drawer waiting to come out the next time I write a letter. All this makes me wonder if we are not in a cycle going between some of the old and some of the new, mixing and matching, fusing and developing and improving, some of the old stuff that has not been replaced will return in some new form with some new purpose. (Alas the typewriter has been fully replaced and simply will not return.) Nonetheless, my tryst with the wax seal was memorable and is something I will keep looking forward to. Perhaps not everything that is vintage is gone forever, and that makes me happy.