Barbie’s world should not be dreamland

A slap-in-the-face commentary on the patriarchy is exactly what we need right now

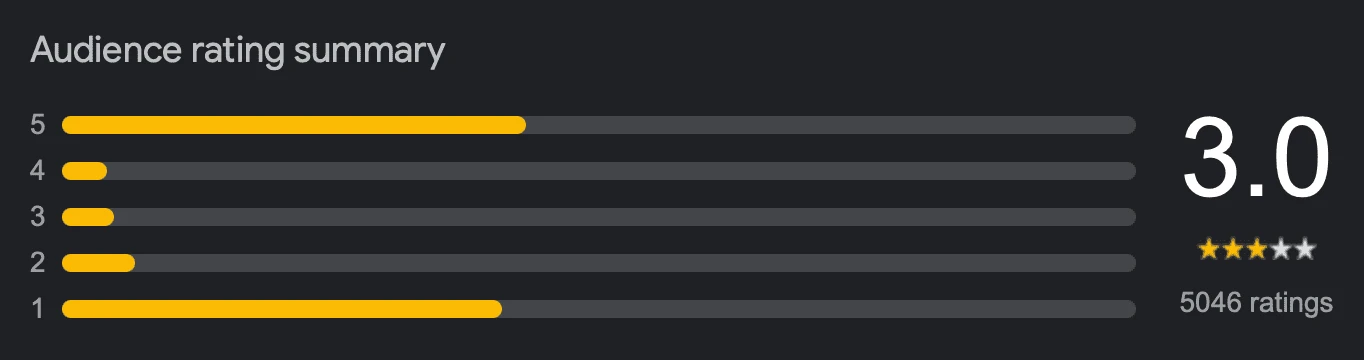

Everyone will identify to some extent with Greta Gerwig’s new Barbie film. We are, regrettably, either living in the patriarchy or are the patriarchy itself. And the film has so far polarised the audience expectedly: audience reviews on Google give the film an average rating of 3.0 with nearly equal 5-star and 1-star reviews. I fall in the former category not because the film is a cinematic masterpiece or because the immaculate Wes Anderson vibes neccesitated by the subject of the film are matched in step by its dialogues; rather I fall in the former category because the film is timely, and it shouts out the ugliest, most obvious traits of the patriarchy unapologetically in a way that will make sensitive people self-reflect and others rile in anger.

There is a patriarch in many of us. It exists in me. My wife and father both claim there is a chauvinist in me and while I disagree, I have deep down often considered that they are perhaps not entirely wrong. The idea is often so deep-seated that to fight it takes enormous presence of mind and questioning one’s every step. It is easier said than done but that is no excuse for it. For my own part, where I recognise it, I will continue to work on being a better person. Unfortunately, those closest to us bear the burden of this.

Humour is often the most effective method of making a point. And Greta Gerwig’s new Barbie film makes plenty of points. We start off in Barbieland—ruled by women and where Kens exist—and soon make our way to the Real World—ruled by Kens and where Barbies exist—when the ‘stereotypical Barbie’ starts having an existential crisis.

The story is merely a carriage for its larger, more thought-provoking message, as indicated by its opening scene, an homage to Stanley Kubrick’s magnum opus, 2001: A Space Odyssey, except with a few kids and a monolithic Barbie this time. Everything else is less about the story and more about the underlying message.

The message itself is not subtle and that is a good thing. It’s slap-in-the-face presence for the entire run time of the film has come decades too late. We have had subtle hints at the patriarchy on screen before, subtler hints at the empowering world of women; but no film has been bold enough to ask outright how men would feel if our roles were reversed with women. What if we lived in a woman’s world? What if we were treated the way men in society treated women all these years? What if men were tossed morsels of rights and powers and opportunities the way women were restricted all this while? What if everything we as Kens take for granted everyday was only available to us in dreamland as they are to Barbies?

The idea is as ugly as it should be, but delivered humorously it makes things feel all the more like a punch in the stomach. As the Kens of the world mansplain to the Barbies and the Barbies humour the Kens, as the Kens revel in their undeserved and unearned social stances while the Barbies merely serve them and cast aside their own worth, you start feeling guilty to identify even remotely with the men in this film. And yet you do. I do. Regrettably, I am part of the patriarchy and it is high time we start making changes from the inside.

In something as simple as Ken’s house being called “Ken’s mojo dojo casa house” or Barbie land being renamed to “Kendom Land” there is both a hint of uncertainty and a sense of wanting everything. In jokes about the patriarchy being about men and horses is a stab at its absurdity. You laugh at a world run by horses, the film appears to ask us, but somehow a world run by men is not just as disgustingly absurd?

In the end, Barbie’s dismantling of male power is delicious to watch even as it hints at a world of absolute equality being the way forward. Margot Robbie carries this film in its entirety while Ryan Gosling adds the right amount of exaggeration to drive home the point of the patriarchy while still keeping things poignant. A host of cameos and pop culture references keep the film flowing at a steady, upbeat pace.

To anyone who has watched Gerwig’s Little Women and Lady Bird, this film comes as no surprise. Her take on life as a woman has always been refreshingly loud and her previous two films were why I wanted to watch Barbie. After all, it seemed like the perfect stage to be even louder about the same topics and this film did not disappoint. If anything, it makes you disappointed in yourself for not doing even more to be better for yourself, for those you love and for society as a whole. Make no mistake, this was likely Gerwig’s intention from the start and she nails it. It is not easy to joke about men or women in a way that does not seem crass while simultaneously also driving home a compelling point that makes you wonder when you let yourself down. But Barbie gets the job done.

Like many other Gerwig films Barbie too contains a powerful monologue delivered forcefully by America Ferrerra playing the sole Real World woman—a mum—in “Barbie Land”. It is perhaps the only preachy moment in the entire film but remains powerful nonetheless. Even if you only skim through my essay, take a moment to read this excerpt from the film in its entirety:

It is literally impossible to be a woman. You are so beautiful, and so smart, and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough. Like, we have to always be extraordinary, but somehow we’re always doing it wrong.

You have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can’t ask for money because that’s crass. You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead, but you can’t squash other people’s ideas. You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman, but also always be looking out for other people. You have to answer for men’s bad behavior, which is insane, but if you point that out, you’re accused of complaining. You’re supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you’re supposed to be a part of the sisterhood. But always stand out and always be grateful. But never forget that the system is rigged. So find a way to acknowledge that but also always be grateful. You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line. It’s too hard! It’s too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says thank you! And it turns out in fact that not only are you doing everything wrong, but also everything is your fault.

I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don’t even know.

Troublingly, Barbie is an escape. It should not be. A world where women need an escape to think of an equal society points to the utter failure of men—men like myself who should do better. Barbie does not preach, it is not a moral tale and you do not book a Friday evening cinema ticket to be lectured to. But, unlike Ken who offers to “play the guitar at” Barbie, this film does not talk at us. It makes us think to the point where the jokes turn into sour reminders of who we really are and the laughter simply drowns our guilt and displeasure. As social commentary, eschewing all subtlety, Barbie is a monumental piece of work.

The hyppocrisy in men’s support of women is pepperred throughout this film but most openly in a scene right at home in Mattel’s headquarters. At the top-most floor under a heart-shaped light sit a table full of men headed by the company’s CEO (played by Will Farrell) who helpfully points out that there have been two female CEOs at some forgotten time in the company’s history and that their several gender-neutral bathrooms exist as evidence of their inclusiveness.

Tokenised inclusion is a classic trick of the patriarchy. Barbie does not hesitate to point this out. Indeed Barbie never hesitates, which makes it all the more powerful. But Gerwig manages to conduct the usual crassness that comes with bold opposition expertly so that the argument underlying the entire film stands out. It makes you ask who you are, question if all your actions have been morally sound, if you have been fair, and if that one harmless gag actually hurt someone’s feelings. Barbie does not defend the so-called “snowflake” but pulls no stops in questioning the perpetrators of the patriarchy—men like myself.

We will look back on the patriarchy in ways similar to how we look back at slavery or colonialism. And those who correct their paths now will find themselves on the right side of history. The film makes me question just how often I have been on the wrong side myself and how I can make things better going forward. To me, leaving the audience with uncomfortable questions is a mark of an excellent film, and in leaving viewers with a myriad thoughts for self-reflection and societal dialogue is a sign that Barbie accomplished all it set out to and then some. Society will not be fixed at the end of this film—and I as a man certainly will not—but we have collectively been shoved in the right direction and for that I will be ever-thankful.

Barbie and her world may be plastic and unrealistic, but everything in this film is very real, poignant, bold, compelling and—for me at least—persuasive.