Battling COVID-19

When the Covid-19 pandemic first threw the world off balance, little did I know I would soon be fighting the disease myself

It started as a deceptively simple feeling of unease. It was the sort of mild body ache that you knew would go away of its own accord. Then came a cold, just as mild, just as eager to leave. None of it seemed alarming. Slowly, the temperature rose, but never so high as to cause alarm. For the first four days, the primary characteristic of the virus that had attacked me was a sinister absence: it never caused enough harm to make you take it seriously.

A silent virus

This is perhaps the single biggest reason why COVID-19 counts are so high across the globe today. When the disease hits, it does not crash the party; it simply slithers in through your door and makes its way around more or less unnoticed until things become overwhelming.

People tend not to bother until one of two things happen: they are cured thanks to a superior immune system; or they fall sick enough that they can no longer ignore it, eventually needing medical attention before either making it back (such was my case) or unfortunately losing the battle (as over one million people have as of the time of writing this article).

By the time I had lost my sense of smell, it was about four days in. Discerning that I had lost my sense of taste, however, was a more confusing matter because I did have a taste. Unlike smells, my tastes had not all vanished. Everything tasted more or less like it should but somewhat bitter. It is well-known that one’s sense of smell enhances their sense of taste, which is why the reverse made sense too: losing one’s sense of smell meant also losing most of their sense of taste. Except bitterness, somehow. This was another reason why I delayed suspecting COVID-19. Some others I talked to who had also got this disease reported completely losing their senses of both smell and taste.

By the fourth day, the urge to get myself tested—prodded in no small part by my wife—was too hard to overcome and so I got in line at a local testing centre. My fever somewhat increased later that day but dropped off by nightfall, perhaps (I fancy in hindsight) so that I could wake up refreshed with the energy to answer a telephone call from the District Health Office informing me that I had tested positive for COVID-19.

A virus behind the scenes

Being largely asymptomatic it was first planned that I would isolate myself at home while others in the house would get tested too (which they did, and thankfully all tests turned out to be negative). This is currently the norm enforced by the local government: quarantine at home as a first resort.

Being largely asymptomatic also meant the path ahead was clear: I would remain isolated for seventeen days, per government regulations, taking appropriate dosages of tablets, and getting enough rest while my body would fight and expel the SARS-Cov-2 virus that was an unwelcome visitor in me.

However, things turned out to be a bit more complicated than that. About three days after my isolation at home began, things started to go downhill again. My temperature rose around the same time I began noticing a sort fo tingling sensation in my chest whenever I breathed deeply. And every deep inhalation was followed by a cough-ridden exhalation.

Over the past few months, having closely followed the ongoing research on this virus, I was aware of two things: people who had this virus had developed lesions in their lungs and, at times, blood clots all over their body. While my breathing remained normal, breathing deep tickled my chest enough that I could no longer ignore it.

A fight ensues

We had planned a few tests to be done after my recovery, including a CT scan that the wife and I, among others, both had in mind. But the tingling in my chest had been conspicuous long enough that I decided that same evening to get a CT scan done immediately. Securing an appointment proved quick and easy thanks to some excellent doctors. By 8 pm I had my scans in hand and was inside an ambulance heading to a dedicated COVID-19 hospital where I would be admitted for observation. Little did I know at this point that there were lesions in two lobes of my lungs causing congestion, and that I would have to spend the entire coming week in hospital, being administered antiviral medication, blood thinners and lots more.

My full diagnosis came to me on my first morning in a hospital bed. Blood thinners would have to be administered, fever will have to be reduced through the usual methods, and my ease of breathing will have to be watched closely.

The morning that followed the night of my admission I had only one thought in mind: I was incredibly lucky to have a supportive family and friends who went out of their way to enquire about my health daily and stay connected with me virtually all through. One can never be thankful enough. But one will also have to spare a thought for those who do not have such a support system. COVID-19 forcefully isolates the infected, like insult upon injury, rendering them powerless not only physically but also mentally. Having a good support system is key to getting through the fortnight or so that this infection gets people down.

The other big problem is how this virus exploits its silence (no doubt by design) to spread quickly. In the hospital I was in was an entire family of infected people with nobody on the outside to take care of them. Healthcare is pretty good so the hospital likely did take care of everything, but their stay was longer and undoubtedly more arduous than mine.

In a close-knit society like India, especially in the lower economic strata, in my experience, an inclination towards familial closeness overshadows quite a lot else. Isolation due to a virus quickly becomes an emotional question of balancing the feeling of abandoning someone and being there for them against all odds. The latter swiftly ensures the new coronavirus spreads across the household in no time.

Treatments and world views

Determining the ideal treatment for COVID-19 is an ongoing affair, but there was little doubt when I was in hospital that a five-day treatment with Remdesivir would be adequate as I was only on the brink of needing oxygen but thankfully ended up not needing it. I remember somewhat dramatically when the doctor unscrewed the oxygen inlets from the wall mounts beside me to make more space for me to move around in bed freely; it was almost symbolic. It is funny how so many mundane incidents suddenly become beacons of hope when one is down. Is our sense of gratitude heightened? Is this humanness in its rawest form? Why, with health, do we bounce back to becoming ungrateful?

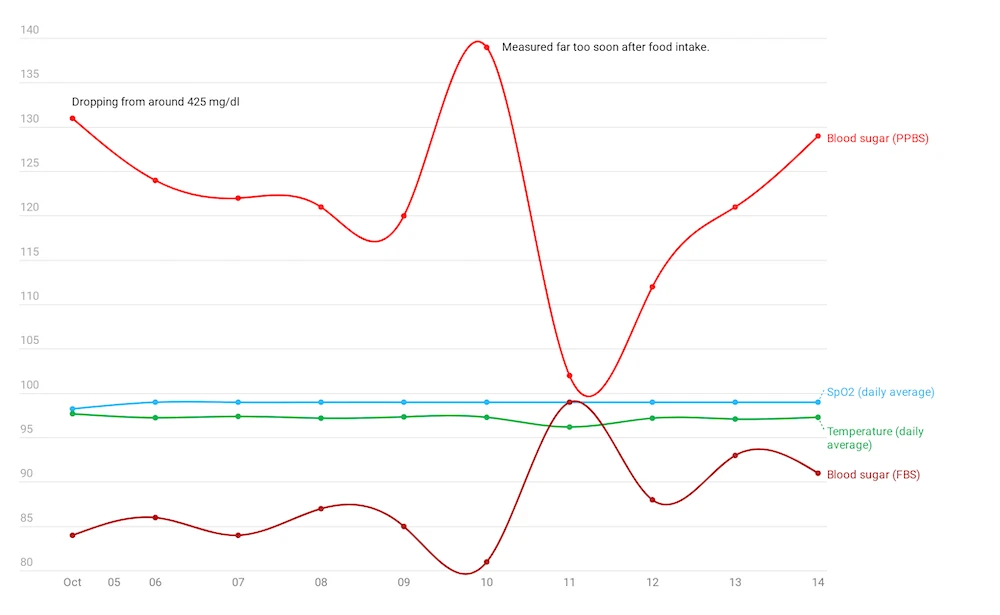

The other line of treatment was blood thinners, because SARS-Cov-2 is known to cause several random blood clots. Additionally, this managed to balance the increasing blood sugar brought on by steroids, an observation that prompted me to begin tabulating twice-daily measurements of blood sugar for the month following my discharge from hospital. (The chart above was made over ten days since discharge and a month is yet to pass since said discharge, so an updated chart will be put up by the second week of November.)

It is said that being down with something one is helpless to fight alone not only enriches one’s world view but also permanently changes one’s approach to life itself. I used to think only a severely traumatic event could possibly do such a thing but I was wrong. While I would not term my experience ‘traumatic’ for lack of understanding of that word, I will say this: actually falling ill with an illness the world was talking about—and I was only ever talking about—gave me a renewed focus on the things that matter in life. In Stoicism we call this memento mori, and people like Steve Jobs and Todd Henry put it well when they said one must do something as if it were the last thing one ever does in life, and if it isn’t worth being part of your legacy, it is worth questioning if the thing is worth doing at all.

I fear this heightened sensitivity will pass. I hope it does not. And my reason for writing it down here openly is to help me recollect, should I ever need it later.

Back on my feet

I have never been one to count my chickens before they hatch. That is one reason why I pushed writing this piece for close to two weeks since my recovery. The other reason was to see if over time I have any new insights about the entire event (I do not).

Quite a few people have told me what I do following my recovery from COVID-19 is as important as the treatment process itself. A key task ahead for me is to consistently hit my spirometer goals and in this I am happily logging improvements. The other approach is to get in a lot of exercise, but not too enthusiastically, and this I am approaching with a good old-fashioned brisk walk. Eventually I hope to return to my daily cycling.

Interestingly, contracting this virus also introduces two specific lines of thought: first, about all of our individual places in society; and second, about our responsibility to society.

The second one is easier to understand: as someone who got COVID-19 it is quite important to know the spread of the virus ended with you. To live with the thought that you gave the virus to someone who then gave it to someone else is hard to say the least. Having been extremely cautious—laughably so at times—knowing that nobody contracted the virus from me was satisfying. This was in large part because I isolated myself from the earliest possible days. I also eventually learnt whom I contracted the virus from and how, but I would not want to get into the details of that without good reason.

The other thought, that of our place in society, is something that has troubled more than a handful of unfortunate families especially in India. Months ago there were reports of victims and their families being shunned—even chased out of their towns one point—for having this infection. Either that died down as the virus became more common in society or the media simply stopped reporting it having found shinier toys to keep their short-lived attention. However, if you thought your neighbours were thoughtful enough to be supportive in such times, you might want to think again. Storms shine light on fair-weather friends.

A lesson for the world

Following Remdesivir the tingling in your chest passes; and following a fortnight of rest slowly morphing into work so does the dyspnea. At least in cases like mine that were severe but not critical. And these are good signs. All this rest has also given my an opportunity to get updated with the ongoing research; things are promising and we will no doubt have a vaccine eventually, but in our haste to have a vaccine in hand it is equally important that we do not sacrifice the stringent scientific boundaries that will make these vaccines reliable and trustworthy.

My other fear is that nationalism (and a fake sense of patriotism) will grip people at an inopportune moment. Right when all we need is for science to be left alone, and perhaps followed and heeded, some countries will leap ahead callously looking for some recognition and with overblown amour propre.

If this virus was in some ways an interesting lesson to me, it is a critical chapter in humanity’s existence. But while we have all been capable of looking out for ourselves, we have always had a poor track record when it comes to learning from our mistakes collectively. Everything has always been someone else’s problem. Not anymore.