‘News is to the mind what sugar is to the body,’ argues Rolf Dobelli

Get ready for crisp and convincing arguments for an extreme solution to a real problem—our obsession with the news.

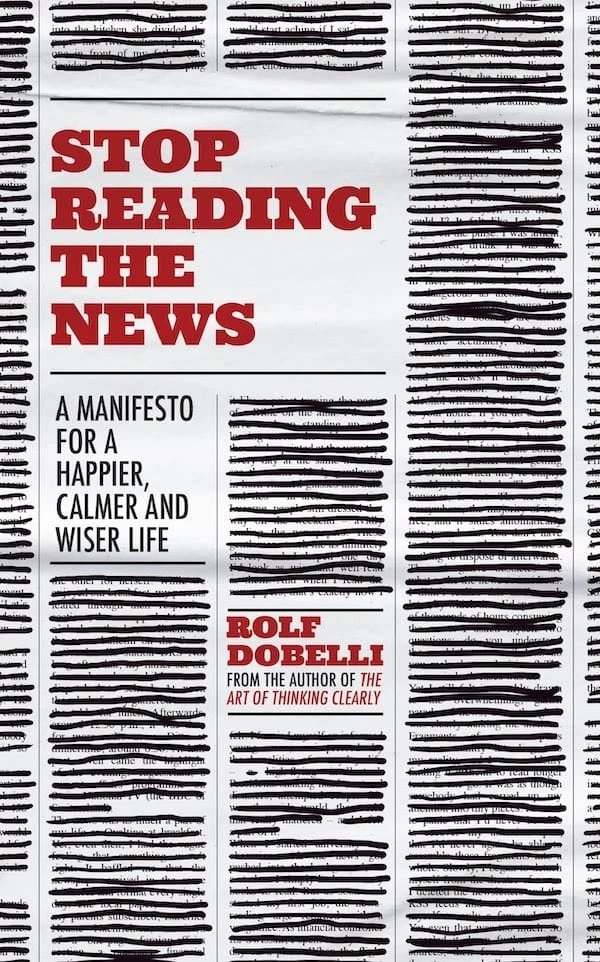

‘To my wife, Sabine,’ starts the dedication on Rolf Dobelli’s short book, ‘who stopped reading the news long before I did. And to our twins, Numa and Avi, who thankfully are still too young for all that.’ These two sentences paint a picture of the sort of life the author wants us all to live: freed from the presence of the daily news in our lives, with no exceptions. In the end, promises Mr Dobelli, we will lead a happier, calmer and wiser life. ‘Digitalisation,’ he says, ‘has turned the news from a harmless form of entertainment into a weapon of mass destruction, and it’s aimed straight at our mental health.’

If the argument made by this book, right in its title, seem extreme, you are correct. The entire book is as sharp as the title is and does not hesitate for a moment from telling you what you need to do right now: stop reading the news. There are no methods catalogued here to help you slowly get away from it all; Mr Dobelli’s approach is to make the choice and quit cold turkey. In fact, he claims, that is the only way. And you will start to notice its effects sooner than you might expect.

News, Inc.

It goes without saying that the core argument of this book is that you stop reading the news; but a bit of clarification is due: the arguments being made are not against awareness but against obsessing over the daily news. And the entire book may be divided into two approaches: in the first Mr Dobelli talks about why giving up the news is important and what one can hope to gain by it, drawing from his own experience and suggesting a couple of techniques on the way (which again come down to quitting cold turkey); in the second he talks about the inherent problems with news itself while addressing one of the biggest arguments for the news to exist—in a democracy, people must be the decision makers and for that the people must be well-informed.

Rarely do I vouch for such an extreme idea but there is a lot of sense in Mr Dobelli’s arguments. He recommends, for example, that reading longer, more carefully researched articles about an event is better than reading the daily news, and I agree: for my own part I have found weekly publications to be more meaningful in the long run than daily newspapers when it comes to understanding the nuances (and there are many) of any event. A particularly interesting thought from his childhood that he quotes in this book goes thusly—

Something wasn’t right. It baffled me that the newspaper arrived in the same thickness and format every single day ... If something happened on an uneventful day it would be treated as important and given centre stage, even if on a busy day it would have been treated as unimportant.

That encapsulates the trouble with the news today. Reading this sentence reminded me of the BBC’s famous broadcast on 18 April 1930 which was simply ‘There is no news’ followed by 15 minutes of a piano song. On the one hand it feels like we can only ever fantasise about such slow news days today, but on the other, as Mr Dobelli rightly points out, less impactful news on slow news days today too would be highlighted like it has a great impact on society. Today, news corporations work like everyday must have a headline and they give stories an inflated importance to satisfy this self-imposed rule.

This all points to the nature of the news today: it is a corporation like any other and monitors—and even manufactures—its output to keep itself afloat. Mr Dobelli explains this quite well pointing out that—

...anything that might pique readers’ interest and boost sales was considered newsworthy by the publishers, regardless of whether it was actually important. This fundamental fraud—the new being sold as the relevant—has persisted to this day.

There are some arguments that this book makes, such as this one, that are immediately sensible, yet there are others (which I will address soon) which makes a lot less sense—a trait that is to be expected in a book this extreme.

A lot of hard hitting

In the title of each chapter Mr Dobelli captures its essence, so I will restrict myself to naming those which I particularly liked, using them to also clarify what arguments the author makes within.

For basic arguments, the news, says Mr Dobelli, is irrelevant; it gets risk assessment all wrong (as we saw with slow news days above); it obscures the big picture (where the author quotes a book of 'Join the dots' puzzles and compares news to the dots, which make no sense unless we add context by drawing lines in-between; see also the quote below).

He takes it further with some hard hitters that anyone who knows the news well enough also knows is true, although we might not always want to admit it: the news reinforces hindsight bias; it gives us the illusion of empathy (think, the now-fashionable cancel culture); it destroys our peace of mind; it produces fake fame and, perhaps most scandalous, it encourages terrorism.

That the news is uninterested in a full picture is described succinctly in the following sentence: ‘News corporations and consumers both fall prey to the same mistake, confusing the presentation of facts with insight into the functional context of the world.’ If you thought this is unintentional, Mr Dobelli clarifies it immediately: ‘...the few journalists who do understand the “engine room” and are capable of writing about it aren’t given the space to do so.’

If my not quoting all chapter titles makes you wonder if I do not back them, you would be right, at least in assuming that I do not back them entirely. Some examples include the claim that the news keeps the ‘opinion volcano bubbling’ (that is a reactionary choice we make), that it makes us passive (again, that is our response to it) etc. My disagreements with this book, however, are dwarfed by my agreements with it.

Breaking news

All that said, there is an important disagreement I have with this book that I would want to single out given the current times (for future readers: this review was written at the height of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic). Says Mr Dobelli, ‘You can safely assume that the more “breaking” the news, the less it actually matters to you’. While this is true in general, it is not at the moment—or at least was not in the second quarter of 2020—when reportage of the COVID-19 pandemic not only forced governments to act but also gave people a sense of what to do and how to respond to the pandemic. It also gave people strength knowing that the whole world was going through this together and that success stories were popping up every now and then like beacons of hope. Without the news, the pandemic would undoubtedly have been handled worse.

The reason I said that this statement would have been true in general, ironically, is apparent when you look at how reporting evolved over the course of the same pandemic: the news has once again embraced its sensationalist tone, given voice to the imporance of the economy over healthcare and generally made a lot of noise that—unlike the pandemic response—has not given rise to enough actionable recommendations at a solution.

On a similar vein, the media in the first half of 2020 helped positively to spread awareness of racial bias in the US (and no doubt in other countries) but really what came of it? Hong Kong was all but sold to China; the news destroyed our peace of mind, as Mr Dobelli puts it, and it made us feel empathetic, which made us feel like we were contributing in some way; but we were really doing nothing but consuming the news while simply feeling active, which is why one piece of news passed on and another came in its place and the world went on as it always has.

This book is a quick read, being more the length of a novelette than that of a novel, and is worth everyone’s time because in some way it will change how you consume the news. It may serve its intended purpose and make you quit altogether; it may make you pause and reconsider the methods you employ to consume the news; or, as in my case, it may at least make you a more responsible consumer of the news. Whatever the outcome, you will find that your time was better spent reading this book than today’s newspaper.