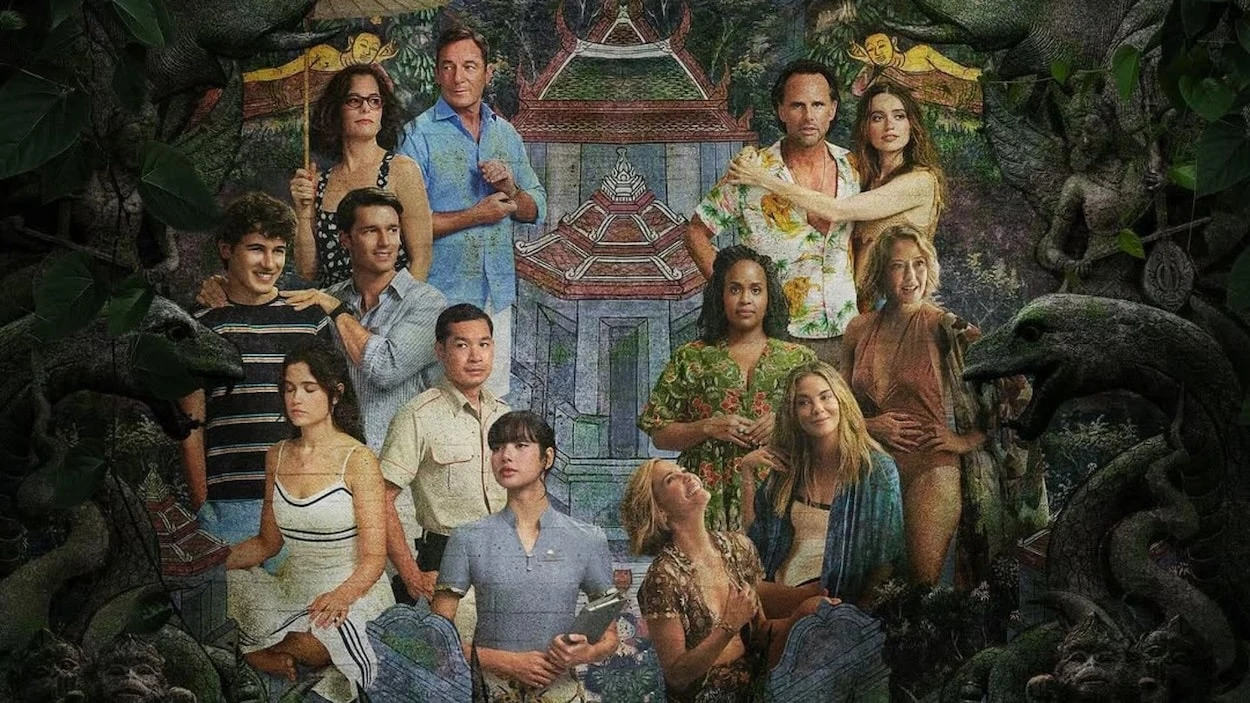

The White Lotus: Season 3

Compelling, and only just misses the mark—Spoiler warning, text may be NSFW

“The source of your disappointment changes but the constant is that you’re always disappointed.”

—Kate (played by Leslie Bibb in Season 3 of The White Lotus)

Returning with its recognisable traits of a strong cast, great writing, bold and baiting visuals, and a Scorsese-esque reliance on music throughout its eight-episode run, the third season of The While Lotus delivers, although with fewer pearls of wisdom and a lot more of what Namwali Serpell once called ‘new literalism’.

Let us start with the characters, who have always been central to the show. Rich people disconnected from reality. The last two seasons contrasted them to The White Lotus staff but there is little of that this time round save for an interesting tale between Mook and Gaitok, both of whom do a wonderful job of being the brief Thai interlude during every episode, speaking of simplicity, ambition, desire and being waylaid.

The questionable friendship of the three forty-something ladies—Laurie, Kate and Jaclyn—is perhaps the most layered, starting off with an almost juvenile desire on the part of Laurie and Kate to stay on their movie star friend’s good side, slowly evolving into jealousy and then straight up meaningless gossip before it diverts unexpectedly into more poignant themes.

The trio struggles to fit themselves into any age group, not wanting to be seen as either too young or too old, but mostly doing all the seeing themselves. In their discomfort they disconnect from their surroundings to the point where one starts to question how much of age is a social construct and how much of it is an individual preoccupation. Each of the three women comes to terms with it differently which also informs how they behave subsequently. It was perhaps a bit of a let down that they all settle on their friendship in the end, but knowing what we do about them, the keen viewer is left sceptical.

The second group of holidayers are the finance family the Ratliffs. The father Timothy, caught red-handed embezzling back in the US just as his boat reaches Thai shores and left spending his entire holiday teetering between life and death, balancing expectant lifestyles, seeking solace from both Lorazepam and a Buddhist monk, and facing the worst dread of them all: expectations. His wife, with an amplified North Carolina accent played by Parker Posey first as a major annoyance who soon became, in my eyes at least, a fantastic replacement for Tanya McQuoid from the last two seasons. Her character curiously lacks motivation but her boundaries become clear by the end while she sits up in bed one night with folded hands praying so that Jesus might save her daughter “from those Buddhists”. It is at this moment that you realise if Gaitok had not stolen his gun back from Tim, perhaps the man would very well have shot his entire family and himself that very night.

And finally we have Chelsea and Rick, the oddest of the lot and somehow also the most normal. Between the owner of the Thai White Lotus, Sritala, and her manager Fabian, who dawdles around the resort and hesitantly exhibitions his singing talent (which, if we go by the brief glimpse we get of it, is pretty good) and her gangster husband whose bodyguards waltz in and out of the resort at will, we have a fairly predictable stage set up for this season.

As with last season, there are elements of this show designed to make people talk about topics they had successfully sidestepped for some time now. Even Jason Isaacs fell for the trap. Following their introduction in season two, the show brings even more prosthetic penises and this time it does so more openly. The show appears to ask that when nude scenes with women are aplenty in films, why is it not so with men? Particularly with the idea of misrepresenting normal male genitalia. As the BBC reported asking why showing male genitalia on the screen still shocks viewers—

There are further issues with using fake genitals on screen, says Fouz-Hernandez. “On one hand, it’s great that Mike White is giving visibility and normalising male nudity,” he says. “And I understand the idea of contracts and that actors might not want to show their real genitals for close-ups, but the use of prosthetics and digital effects is disappointing, because in a way, they defeat the purpose by contributing to perpetuating the very phallic imagery that male frontal nudity could debunk, creating an unrealistic representation. It would be good to see more realistic diversity of sizes and shapes… The series is therefore perpetuating the phallic mystique by revealing a penis that isn’t even real, which is problematic.” (emphasis added)

Women have fought unrealistic representations for decades now, so there is little in defence against it when it is done for men. If anything, its most meaningful outcome may be to ensure all nudity on screen turns more tasteful and less exploitative going forward. It remains to be seen, of course, whether a famously tone-deaf industry drowning in an increasingly malicious political environment will take note.

What appealed to me greatly about the first two seasons of The While Lotus were how much it left open to the viewer’s interpretation. I distinctly remember sitting down to discuss episodes with my wife during and after the fact, and both nodding in agreement and propping up differing interpretations at every stage. With the latest season this reduced almost completely. Films and television shows lately seem to be too nervous about letting the audience interpret anything at all for fear of a backlash. They would rather make their messaging safe and clear, so their revenue streams stay intact. Could HBO have gone this route with The White Lotus?

Writing for The New Yorker Namwali Serpell discusses this growing practice in films and TV where everything is on the nose. ‘Beating at a dead horse’, Namwali calls it, or more eloquently ‘new literalism’. Consider this incredible description of what is going on today, a trope to which I think The White Lotus also falls:

Artists and audiences sometimes defend this legibility as democratic, a way to reach everyone. It is, in fact, condescending. Forget the degradation of art into content. Content has been demoted to concept. And concept has become a banner ad.

The third season of The White Lotus adheres to its concept, but in following up its predecessors misses the trees for the forest. It gets the general feel, the sweeping generalisation and the idiosyncratic characters right. But there was more to The White Lotus in the first season that this latest iteration fails to capture: an abstract openness, a complexity that went far beyond the story we watched on our screens and sat down with us on our couches as we felt compelled to continue living through the lives of the people we had met on screen; people so disconnected from us with whom we wanted to connect anyway.

In my review of the second season I praised the show for offerring viewers “more of the same, not something unrecognisably different”. This time round, at risk of sounding conflicted, I should say the departure was ever so slightly in the wrong direction. Perhaps the next season will redeem itself and drag us back to the substance of the show’s debut year. This season Mike White clearly played safe, which is not what The White Lotus was ever known for. It is more disappointing when you learn that a transgender character reference was removed from the show, which would otherwise have made an excellent addition to the brief verbal political skirmish between Laurie, Kate and Jaclyn.

Arguably the most disappointing plot point of Season 3 was the whodunit. In the previous two seasons the lead up to the death is unexpected bordering on weird; but this time round it is more straightforward, even formulaic. It is no longer about circumstance or happenstance but straight up gangsterism. And that is, unfortunately, all there is to it. The fact that the whodunit did not matter was at the heart of this show, and was what led it its surprising outcome which, in its third iteration, fades away.

Some viewers may interpret Greg’s plotline as a red-herring but if you remember anything from the first season Belinda is not naïve and she finds her way around things in spite of her omnipresent initial hesitation, so of course she was going to cut a deal with Greg just as she had with Tanya, only this time fear replaces her blandishment.

Even though this was not the strongest season of The White Lotus, I continue to remain a fan of the show, and I continue to look forward to more episodes. After all, even when it stumbles, The White Lotus remains more watchable than most shows on TV today.