How to build a zettelkasten system

The principles and specific steps to get you well on your way to building your own knowledgebase

The idea of a ‘knowledge management system’ is all the rage these days and among the most popular of these methods is the zettelkasten, pioneered by Niklas Luhmann, the late sociology professor at the University of Bielefeld. The trouble with most online explanations and guides is that they are overly focused on either the software they use to build out their ‘KPM’ or the fascination of being able to see a ‘graph’ of all their notes, referring to a mind-map of sorts that many products offer as a highlight feature.

It is worth remembering in such times that the zettelkasten of Luhmann was built using boxes and index cards. It is perhaps time we returned our focus to understanding what zettelkasten really is so that the digital implementation we make can be our own and actually make sense rather than seem like an esoteric exercise. Lastly, if you are not a German speaker, every time you feel lost, keep remiding yourself that zettelkasten simply means ‘slip box’—a literal box of slips.

There are three points to keep in mind as we begin: first, it helps to explore zettelkasten not from a technological standpoint but from the perspective of its many principles; second, we did not really know of the zettelkasten during its inventor’s lifetime or from its inventor beyond his own notes-to-himself on it, so whatever we do know about this method is inferential; and third, it appears that Luhmann recognised that ‘others work differently’1 which can be interpreted as his permitting us to make zettelkasten ours—but to do so without first understanding its principles would be a fallacy. We will therefore talk principles first and method next.

The principles

Networking is the core idea

At the heart of every system is a simple nugget of belief that drives and constructs everything else we know about that system. For zettelkasten this is the concept of networking.

In his book, Ahrens quotes Charlie Munger while talking about the idea of learning a network of information rather than a linear list of facts. “We know today,” he says, “that the more connected information we already have, the easier it is to learn because new information can dock to that information … [if facts] hang together in a network of ideas, or ‘latticework of mental models’ (Munger, 1994), it becomes easier to make sense of new information.”

There are two approaches that zettelkasten derives from this:

- Remaining unorganised. Eschew hierarchy and structure in favour of networking or linking. Most other methods to information management rely on planning out a structure or organisation; this is not only forceful but also makes it impossible to discover connections between ideas that you did not manually set-up yourself.

- Keep notes brief and concise. Linking becomes harder if you are looking to connect a dozen essays; it is much more palatable when you are connected simple ideas, claims or facts that do not each take more than a couple of sentences to describe.

Think about the future

Zettelkasten is not a note-taking method. It is a method of organising information you have collected—from books you read, videos you watch, conversations you have etc.—which necessarily means you are not taking notes for later reference or binning, rather you are doing so to exploit indefinitely. Your zettelkasten is intended to outlive you, carrying a piece of everything worthwhile that you ever read, listened to or watched.

A note you take today ought to be with you for the rest of your life and not until the end of a project or book reading or year. The fact that the ultime destination of our zettelkasten notes is called the ‘permanent’ box should have told us this already.

Once again, Ahrens puts it succinctly: “Ask yourself, ‘When and where do I want to stumble upon this idea again?’” So, in addition to being unorganised, being liberal about metadata is important. Link a note to remotely connected notes too if the thought occurs to you. Or tag your notes2 liberally—it does not take too long.

Make it a daily habit

Zettelkasten is a bit like inbox zero in that it is a beautiful thing to have but takes conscious, consistent effort. And by consistent I mean daily. You have to make it a point to ritually either end your work day with Zettelkasten or begin it that way.

Most people prefer to end their work day with it but I prefer to begin my day with Zettelkasten for two reasons: one, it helps me start my morning by recalling yesterday’s readings which adds some connectivity for today; two, it helps me sleep on my thoughts and ideas from the previous day and effectively think them through better before committing them to my permanent notes.

The ‘habit’ part of this method refers to the final step—the transition from literature notes to permanent notes—and not the first two steps of making notes and preparing literature notes: those simply have to comprise your workflow itself.

Make it a conversation

For our last principle we shall refer to Ahrens again who describes the first step in the zettelkasten method beautifully as writing down (notes) to have a meaningful conversation with the words we read3.

I would extend this analogy: during its many stages zettelkasten is a series of conversations. First you converse with what you read; subsequently you have two conversations with yourself. The whole process described in this way may seen tedious but when you think about the actual work that goes into it, the nature of the work, and the outcome of this effort, it becomes a pleasurable activity.

Retrieval is key

There is little to zettelkasten if it is all about throwing things into a box without any way to pick them back up or re-trace them again. The physical method resolved this by numbering index cards in sequence: X for an idea, Xa for a related idea, Xb for another related idea, XaY for a further related idea from Xa and so on. Imagine writing 90,000 index cards as Luhmann did only to have no way to retrieve the one you wanted when you wanted it.

Digital versions of zettelkasten understandably make this steps considerably easier. You can write in markdown and use [[wikilinks]] to link across notes, including to specific paragraphs in some programs, and automatically have those notes link back to this one (called back-links) so that when you want to retrieve it, you just need to start somewhere and your fancy zettelkasten system can take you everywhere else.

What this means simply is that every note must have a link to at least one other note. This harks back to the principle of networking from earlier. And what if your note legitimately has nothing else to link to, such as when it is a brand-new topic? That is where maps come in—see subsidiate steps below.

Hoarding is the way

Unfortunately, zettelkasten makes a case for hoarding. This is a problem physically but should not even be a topic of discussion digitally. Let us instead look at hoarding as a principle of zettelkasten.

Most note-taking approaches rely on decision-making when it comes to taking a note i.e. you place your note in a hierarchy or organisation system when you first take that note. Zettelkasten does away with this entirely. Instead all notes are assumed to be (a) useful at some point in time and (b) useful in ways you did not—cannot—foresee just yet. In other words, keep everything and you can afford to keep everything because you do not have to worry about structuring things.

With the principles clarified, we can finally address the question as to what precise steps the zettelkasten method entails. As we go over this, a few pointers: I use a digital system for my notes as do most others, which is why these steps are digitally-biased; if you fancy a paper-based system, you can still implement the same steps and the accomodations you would then have to make will be obivous; I would, if someone asked me, recommed the digital approach simply because of the many undeniable benefits a digital system brings that far outweighs any of its pitfalls; and lastly, feel free to make it your own—this is neither the method nor the best method, but it is what I have found to be no-nonsense and straightforward.

When you sit with the same system and repeat the same routines every day, you want something that gets the job done effectively above all else.

The method

Step 1: Fleeting notes, or collecting information

We consume information all the time and in many forms—sometimes too much of it. The idea of zettelkasten is to keep note of everything you consume that interests you. This has two benefits: first, and the more obvious one, it lets you retain what you liked so you can come back to it later; second, the critically divisive one, it forces you to reconsider what you want to consume at all4.

The next time you are reading, talking to a friend, listening to a podcast, watching a home video or documentary or film, be armed with a notebook, paper or app in which you can take down quick thoughts. In the zettelkasten system these are called ‘fleeting notes’ and can take many forms depending on the type of content and the context in which it is being consumed:

- If you can return to the work you are consuming, as in a podcast or video, make an indirect note, such as of the time code or simply bookmark the instance around which you saw or heard something of note

- If it is an eBook on your Kindle, highlight it to save the highlight automatically for later reference; make a quick note if needed, if the highlight does not speak for itself or if you have an associated idea not covered by the highlight

- If it is a book, make a quick note of the paragraph and page number for longer notes or exact quotes along with a short-hand description of your thoughts; for briefer thoughts, just note them down in their entirety (a page number may not be needed here)

- If it is a conversation with another individual, scribble while you speak or listen, or excuse yourself and make a note in shorthand on your phone; the same would apply to lectures, wokshops etc. where the speaker would not pause for you

The core idea of a fleeting note is for the action of making a note to take place without hindering your consumption of some content and to enable you, where possible, to return to that content should you need to do so later.

Step 2: Literature notes, or summarising information

After you have finished your consumption, you need to set aside some part of your day to summarise the information. This serves two purposes: it forces you to explain things so you can identify what you do not understand; and, where possible, it forces you to return to specific parts of the content that are worth a second look.

Needless to say, if you can or should go back to the content, as with the time codes you noted down or highlights from your book that you marked for re-reading, now is the time to do so. For everything else, write from memory.

The point of zettelkasten at this stage is to summarise in your own words and not to copy whatever text you read or words your heard. This makes you think about it, ensures you understand it, and opens the doors to new ideas and thoughts that might come to you while you write down what are termed your ‘literature notes’ .

Literature notes, also called reference notes, contain all your takeaways from (usually) a single ‘event’. Such an event could be reading a book, watching a documentary, listening to a podcast etc. Ideally, you will save as much meaningful information as you can about the data in a reference note, such as which page you found a quote or idea, what time code you listened to a curious mention and so on, drawn from—as you probably guessed it by not—your fleeting notes.

If you have ever taken an orientation course at university on academic integrity, this practise would have been emphasises to you multiple times. It should come as no surprise given zettelkasten was born in academia.

Step 3: Permanent notes and back-links

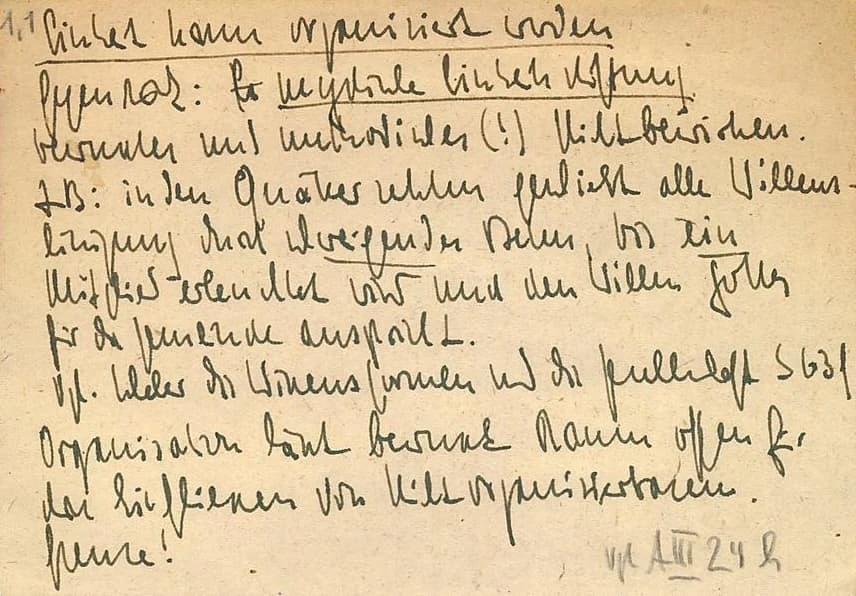

When Luhmann was preparing his permanent notes i.e. the ultimate destination of a zettel5, he used to mark each note with an index number in the top-left corner:

This is a case where digital apps can be objectively superior. You can do away with this concept entirely, relying completely on [[internal linking]] for your notes if you use a program that supports it (most do). But since you have to title your notes anyway—even if only as the file name—you can keep your filename more descriptive as an added advantage.

I use #####-author-concept as my basic file name structure. The hashthorpes in the begining stand for a serial numbering scheme that I use to be able to sort my notes chronologically. This is how I work, not how zettelkasten needs you to work. The point here is that you are free to choose how you handle such specifics so long as you follow the other basic steps outlined in this article. Comments on how I do things are only to serve as food for thought.

Permanent notes are supposed to be ‘bite-sized’, the smallest meaninful length to which you can break down ideas from your literature notes. Another way to look at this is that each permanent note must contain only a single idea along with one or more internal links to other permanent notes and/or bibliography note and/or map, as well as the literature note whence originated (bibliography notes and maps are discussed below).

These components of a permanent note are non-negotiable to ensure that when you do need this note again, you know where you got it from and how you arrived at the idea, to both spark new thoughts and allow you to attribute ideas to their origins correctly.

While several text editors have now come to offer [[wikilinks]] as standard features that work perfectly for internal linking, some programs have set themselves apart for also offering back-links. For instance, if you link to note x from note y, the program automatically marks a list of back-links showing on note x that you have linked to it from note y. This is a great feature that prevents manual back-linking. But it is also there when you do not need it, which has led some to conclude that back-links are anathema in general and can cause people to go down the rabbit hole of internal back-links. I disagree with this black-and-white outlook: so long as you are conscious of what you do—which is central not only to zettelkasten but to life itself—you should be fine. And if too many back-links cause you to lose your orientation, you should go check out what we call the internet.

A note on timelines The above three steps are the primary steps involved in zettelkasten but subsidiary steps exist (discussed below). However, at this point it is worth discussing briefly how long your notes last and how many folders you will really have, considering we are working digitally. Ideally you would have three folders with an optional fourth for bibliography. The three folders, as you may have guessed, are for fleeting notes (I call mine an ‘inbox’), literature notes and permanent notes.

Your fleeting notes are to be discarded daily once they have all been expanded into literature notes. Your literature notes often correspond to your bibliographic entries with one note per reading source; but you could also have one note per reading session or topic or project. My suggestion is that you keep this open and use what works for the task at hand rather than resorting to dogma for the sake of it. Your literature notes are permanent but not networked. And you should work on them daily or as your fleeting notes demand.

Finally, your permanent notes are permanent, bite-sized and networked. You should work on these daily as well, as you make new literature notes, but I prefer to work on permanent notes the morning after for reasons described earlier, which is still technically daily.

Subsidiary steps &c.

Bibliographic references

Niklas Luhmann kept two boxes, not one. The first is the main zettelkasten which would correspond to our three-step, three-folder procedure outlined above. He kept a second box for bibliography according to Sönke Ahrens:

“I make a note with the bibliographic details. On the backside I would write ‘on page x is this, on page y is that,’ and then it goes into the bibliographic slip-box where I collect everything I read.” (Hagen, 1997). But before he stored them away, he would read what he noted down during the day, think about its relevance for his own lines of thought and write about it, filling his main slip-box with permanent notes.

Digitally, this seems to translate to four folders but it need not be this way. The physical bibliography folder can simply be your literature notes folder and it would have clearer rules than all the others: one file per work (per book, per episode, per documentary etc.) and containing the title of the work, names of the author and editor, title of the book or compilation, the publisher, year, edition, URL, date of access and any other data you would normally list in academic references. And of course all your notes related to that work.

Handling internal links to your bibliography folder can be tough if done manually, so prefer programs that handle back-links for you to make it a breeze. With a proper bibliography folder you have a list of all the works you have ever referred to. Name it something like author-year and you have a nice bibliography listed by author. You can also use a generic, empty note exclusively for back-links; consider this you main bibliography index.

Maps of Contents

A slightly more advanced zettelkasten technique, and one that has no connection to Luhmann, is the special type of note called a Map of Contents or simply MOC.

These are useful if you want to further organise your zettelkasten by preparing a map of related ideas. You could, for example, store everything related to a specific experimental technique or new code standard or fringe idea in socialism all in one note which in turn links to several permanent notes.

You can probably see why you need not worry about this too much when starting out. Zettelkasten has enough working for its network as is, so when you really need something more you will know.

Remarks on information flow

Zettelkasten has no structure, just a web of organic links to and from notes. The only thing even resembling a structure can be found in the flow of information from fleeting notes up to permanent notes. These are some observations worth keeping in mind:

- Fleeting notes and literature notes have a many-to-one map

- The fleeting notes folder should ideally be empty

- The literature notes folder is one of two permanent zettelkasten boxes

- Literature notes and permanent notes have a one-to-many map

- The permanent notes folder is the second permanent zettelkasten box

And now some observations on the nature of each stage:

- Fleeting notes are direct quotes and passing original thoughts

- Literature notes are exposition intended to crystallise your understanding

- Permanent notes arise from the dismantling of your understanding into ideas as you comprehend them—not explanations, pure ideas—to be linked to other ideas

Stepwise example

To erase any sign of confusion, here is a stepwise explanation that boils all the ideas above into seven simple steps:

- As you read or listen or watch, take down notes wherever convenient

- Once you are done—or once daily—create (or update) a note in your bibliography folder titled

author-yearfor a single book, podcast, video etc. - Write down any reference details about the work you read, listened to or watched

- Link to the bibliography index cursorily

- Convert your fleeting notes from step 1 into literature notes in the note you created in step 2

- Break down your literature notes from step 5 into any number of ideas labeling each as

short-description-of-ideaand making sure to link each idea back to its literature note

Steps 3 and 4 are performed just once per ‘thing’ you consume. The rest can be done in one sitting or in multple sittings, but, even if you spreak a sitting across two days, it is important that you sit down every day for zettelkasten. Having intimate knowledge of your notes, not memorising them, is critical to a successful zettelkasten system.

Apps? What apps?

This question is the elephant in the room every time zettelkasten is discussed. Most people build their zettelkasten digitally these days and, while ideally any text editor should do, for effortless back-links you need a program that supports a two-way internal linking mechanism of some sort.

Caveat emptor but here is what app I would recommend and why: I have simple requirements from a program intended for zettelkasten, including platform agnosticism, markdown support and back-link capability. (And of course I’d love something with a free version so long as it has a solid business model.) Notion gets disqualified on the very first count; Logseq on the second count6; and iA Writer on the third count. My choice therefore is Obsidian and it is what I use with iCloud sync across all my devices.

That said, the beauty of zettelkasten is in its principles and system, not in the specific tools you use. Some tools can make some tasks easier but feel free to use what works for you—more important, do not get hung up on tools or spend too much time customising them. After all, zettelkasten is intended to help you get more out of your content consumption, not to keep you from consuming at all.

From a remark on Luhmann’s note to himself, digitised by the University of Bielefeld. ↩

One of the best enhancements made by digital programs for zettelkasten is, in my opinion, being able to tag notes. This introduces a added level of networking not otherwise present in standard zettelkasten but in its nature enhances the core principles of this method. I do not consider back-linking a digital enhancement because you could do that physically anyway; however, it would have to be done manually, which makes back-linking a digital convenience instead. ↩

In 10.1 Read with a pen in hand, “…to have a meaningful dialogue with the texts we read” are his exact words. ↩

If you ask yourself, “Is this something I would want to read, watch or listen to while making fleeting notes about it?” and use your answer as an indicator of whether you should or should not go ahead with this piece of content, it can be a useful method of filtering out unnecessary consumption. This is not universal as we may want to consume casually sometimes, but if you find ourself asking this questions 147 times a day before opening a new reel on your favourite social media website, you can be sure something needs to change. ↩

This sort of thing divides rooms but I prefer to call a note in my zettelkasten as a zettel as opposed to a note which is a generic note everywhere else. The tougher, but pointless, debate is what the plural of zettel is; many opinions seem to exist on this seemingly banal question, ranging from the more German-sounding zetteln to the more English-sounding zettels to the more meditative zettel as if it were a plurale tantum. ↩

Logseq has a lot of weird drawbacks. I will not list them out here but Chad Kohalyk did a great job of overviewing Logseq in comparison with Obsidian. Chad sums it up in the end quite nicely too: “If you don’t need a writing app, and are just looking to link knowledge and be productive, especially if you are just on a single device” you should get Logseq. For me particularly, Logseq fails for these very reasons. I write a lot in my zettelkasten and use it across devices and also prefer the simplicity of Obsidian to the tighter workflow pushed by Logseq. ↩